10 Things You Need in Your Product Requirements Document

What makes a perfect Product Requirements Document (PRD)?

Just like a Product Manager, a product requirements document needs to perform many different roles simultaneously and effectively. This document will be consumed by designers, marketers and engineering teams, and needs to communicate all the necessary information they need.

In reference to the comic above, our product requirements document helps ensure that everyone is looking at the same tree. All you need to do – is think about the reader, and pre-empt the questions they will ask.

Before we start, note that I’ll use the term product and feature interchangeably in the notes below – while they don’t mean the same thing in real life, it doesn’t change much for the product requirements document.

Let’s jump in.

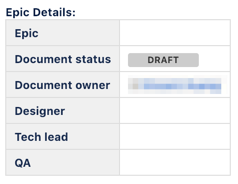

1. Document meta data

Like any great book, a product requirements document should be timeless. If someone has a question about the feature you are building at any time – this document should be easily searchable and scannable.

Say in 6 months, testers find a bug related to your product – the developer in charge of this fix will need to get up to speed on intentions behind this feature, and the people involved (in case they have more questions).

This section can include version number, contributing stakeholders, important dates, and a link URL of the epic/task.

2. Background and motivation

This is the why behind your product. Be assertive, but brief - treat it like an elevator pitch. If possible, throw in some impact estimates like:

“this feature is expected to save 10 hours per month for the Operations team”

OR

“…improve engagement rate by 30%”

If your stakeholders are spending a non-trivial number of hours working on this product - they need to know it’s worth it.

3. Existing data and user-research

For more complex product - you’ll want to include the data about the current state. If you are doing some user research in the pre-specs stage, you’ll want to include a summary of this as well.

For example: if you are redesigning the checkout flow, describe the current payment funnel behaviour and the drop off rate at each step. If you have surveyed people who have abandoned cart - provide a brief of the main learnings.

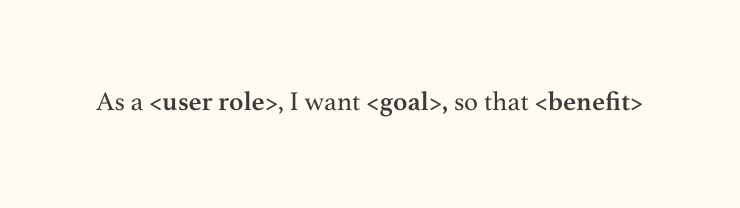

4. User stories

A user story is a unit of development which can be independently estimated and serves a distinct need or purpose for your end user. You should be able to easily tell if a user story has been satisfied or not.

Break your high-level goal to its constituent stories and describe the implementation logic briefly. Assign priorities to each. Be more detailed with high priority stories. If task tickets have been created, link to these here.

Here’s a handy list of things to keep in mind while writing user stories.

5. Design specifications

This is the most crucial part of your product requirements document, which your developers will spend the most time on.

Map out the user flow (I’m a huge fan of draw.io and include mockups for screens if you think it’s valuable. Link to high fidelity mockups where applicable.

Don’t be afraid to head to a whiteboard or grab a paper and pen if it helps you save time.

6. Feasibility assumptions and known edge cases

The hallmark of a great PM is the ability to pre-empt questions from their stakeholders. This helps reduce the back and forth between teams and move the product implementation along.

Mention the assumptions you have made about user (and system) behaviour while writing the specs and what the intended behaviour should be when certain edge cases are encountered.

For example: you might choose to implement a payment flow where a user does not have to create an account before making a payment - but rather just entering their email. The underlying assumption is that users will not intentionally make a payment using an unknown person’s email address. If a user erroneusly enters the wrong email and makes a payment – the operations team will rectify this manually.

7. Data storage and third party integrations

When users interact with your feature, describe how you want this information to be stored - whether that’s in your own database or in a third party tool. In many organizations, this is handled by developers - in which case, work with them to add this in.

As a PM - even if you’re not doing this yourself, it is beneficial to know how this data is stored so you can track the performance of this feature later.

8. Acceptance criteria

These are the conditions that the product needs to satisfy in order to be accepted by the user (this can be a customer, internal team member, or system - if you are working on a system level feature). This is critical for developers and QA engineers - since they will be using this to write test cases.

Well written acceptance criteria should be:

- Simple to read, with a clear definition of “doneness” (pardon the cooking analogy)

- Written before development work begins, so that the customer intent is not diluted by the realities of development

- Focused on the WHAT - not the HOW. It should describe the intent and not the solution

9. Success metrics and measurement

Focus on one primary metric that you are looking to improve with your feature. For example, if you are redesigning your checkout page - you should track your payment funnel conversion rate.

You can mention other secondary metrics that might be affected by your changes - e.g. time on page, average order value etc. - but these are not critical.

Mention how you plan to track these metrics - even if you don’t paste in the actual queries and dashboard links, this will save you some time when you follow up with the team about the success/failure of the feature.

If you are looking for frameworks to help you define your metrics – here’s some reading that might help.

10. Negative scope

Just as you need to be clear about the features you want to implement, you need to emphasize what is out of scope.

This is another area where you should anticipate questions beforehand and clarify these as early as possible. This reduces back and forth during the review and development process, and keeps the team’s eye on the ball.

Remember…

A product requirements document should be an extension of an extension of a Product Manager - a living breathing thing in many ways.

Be as succinct, empathetic and exhaustive as you can be in your documentation, and your stakeholders (and managers) will love you for it.